My questions about identifying works of landscape urbanism has its first lead. A reader (and fellow former North Dakotan Brook Meier – an architect now practicing in India) offered some projects worthy of explanation. He used to work for the firm LA Dallman in Milwaukie, Wisconsin and mentioned the collective Crossroads project, which he succinctly summed up as “A multi-part urban story that links transit-ways and neighborhoods while creating something out of nothing.”

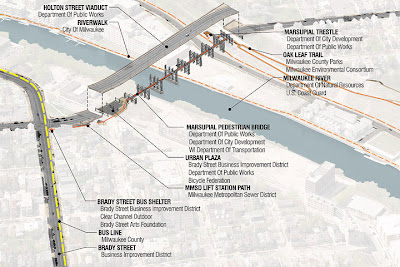

The project consists of three parts, The Marsupial Bridge, The Urban Plaza, and the Brady Street Bus Shelter. As three distinct projects, the have are solidly formed pieces of landscape architecture, and urban design – with the infrastructure of a bridge thrown in for good measure.

:: images via LA Dallman

These projects were not planned as a cohesive work of landscape urbanism per se, but form an assemblage of projects that start to take on some of the characteristics of landscape urbanism, including providing a diverse connective tissue (Wall, 1999b) of disparate elements, being opportunistic in looking at context to drive design decisions, incorporating a ‘civic infrastructure’ (Poole, 2004b) and embracing elements of indeterminacy in flexible programming of the central public space, giving what Waldheim would refer to as “imaginatively reordered relationships between ecology and infrastructure.” (Weller & Musiatowicz, 2004: p. 66).

A look at the three elements of the project give an idea of the elements.

Project 1. The Marsupial Bridge

“The Marsupial Bridge is a pedestrian walkway that uses the existing Holton Street Viaduct structure as its “host”. The bridge weaves through the existing structure that was originally engineered to support trolley cars, a transportation system which was abandoned with increased automobile use in the early 1900s. Hanging opportunistically from the over-structured middle-third of the viaduct, The Marsupial Bridge responds to the changing transportation needs of the city by increasing pedestrian and bicycle connections. The bridge is a “green highway” that activates the unused space beneath the viaduct, encourages alternative forms of transportation, and connects residential neighborhoods to natural amenities, Milwaukee’s downtown, and the Brady Street commercial district. The Marsupial Bridge’s undulate concrete deck offers a counterpoint to the existing steel members of the viaduct, inspired by the notion of weaving a new spine through the structure. Recalling the wood docks along the Milwaukee River, formerly an industrial corridor linking northern territories with the Great Lakes, the concrete deck is finished with wood deck and handrails, and stainless steel stanchions and diaphanous apron. Floor lighting is integrated behind the apron, and precision theatrical fixtures are mounted above to create a localized ribbon of illumination with minimal spill into the riparian landscape below.”

Project 2. The Urban Plaza

The most well known of the three, which has been covered in some of the mainstream press, is the Urban Plaza segment, nestled under the end of the bridge abutment.

“The Urban Plaza converts an unsafe underbridge area into a civic gathering space for film festivals, regattas, and other river events. The position of the Urban Plaza within the existing viaduct presented an unusual challenge due to the lack of natural daylight for plant growth. Accordingly, this area could not be defined through landscape design in the conventional sense; rather, concrete benches are set amidst a moonscape of gravel and seating boulders. The benches provide a respite for pedestrians and bicyclists as they make their way across the Marsupial Bridge, and by night the benches are lit from within, transforming the Plaza into a beacon for the neighborhood. This strategy challenges the traditional notion of public space as a “town square,” or “village green,” and provides a site-specific program for the underbridge zone.”

Project 3: Brady Street Bus Shelter

“The Brady Street Bus Shelter serves as a waiting station for city bus passengers, bicyclists and pedestrians, and marks the gateway between lively Brady Street and the new Urban Plaza and Marsupial Bridge. The shelter is set within a platform defined by concrete and stone walls that are shaped and folded to serve as benches, retaining walls, and structural elements. Mahogany benches rest upon interlocking concrete and steel supports, forming an L-shaped plan that invites varied seating positions and protects users from the elements while allowing clear views to approaching buses. Large steel sash glass panels serve to block wind and frame views down the connecting Lift Station Path, and wood wraps the steel elements that come into direct contact with the occupants. The Bus Shelter collects rainwater through a butterfly roof, which drains into a cast concrete basin below.”

|

| Click to ‘activate’ the image |

Great post. Your readers will certainly learn a lot from posts like this. Thank you for your effort.

I’m interested in your content and have added a link to my blog:

thecityspace.blogspot.com

Hope that’s ok. Check out the space, let me know what you think.

Jason, this looks like a great project – thanks for telling us about it!

You can read about this project in Princeton Architectural Press book “Small Scale: Ideas for Creative City Living.” Great book, great read, and awesome project.

This looks very cosy – would love to watch some gritty film noir here