I warn the reader that my take on the recent NOWurbanism lecture featuring Chris Reed, Randy Hester and Howard Frumkin may be skewed by a really bad cold and the influence of massive doses of cold medicine, along with spilling an entire water bottle inside my bag that literally muddied my notes into a semi-decipherable pulpy mess. As all histories are individual, this will be my reading of the nights events (and I fear I will not do them justice). But then again, perhaps this is the perfect storm of dissociation in which to warp and skew the voices into a coherent narrative.

I was really excited to hear from Reed, Principal at Boston-based Stoss Landscape Urbanism and adjunct associate professor of landscape architecture at Harvard GSD. As recipient of the 2010 Topos International Landscape Award, “…in recognition of the “theoretical and practical impulses the firm provides to the advancement of landscape architecture and urbanism as dynamic and open-ended systems.” As a practitioner who embraces the project-oriented aspects of landscape urbanism, I think Reed is unique in straddling the line between theory and praxis – and approach that is often attempted, but rarely done in a legible way. I was keenly focused on finding out the methods for achieving this balance.

Ecology.Agency.Urbanism

The bulk of Thursday’s time was given to Reed’s lecture entitled ‘Ecology Agency Urbanism’ in which he frames landscape and ecology in a context beyond the current concepts of ‘sustainability’ and ‘LEED’, arguing for the ‘agency of ecology’ that is not used as a palliative but as an instigator. In our search for a positive performative approach, we often rely on the crutches of simple definitions or rating systems, which move towards luke-warm, incremental changes, but not paradigm shifts.

Some History

Reed first frames some of the historical elements of ecology as it relates to planning and design, mentioning Ian McHarg‘s ecological assessments (inventory, mapping, overlay) and giving value systems to data to use for design and planning-based decision-making. While acknowledged as important in elevating the discussion, there is also the flip side of criticism’s of this objectivty and quantification of processes, alluding to the lack of a cultural lens in which to perform interventions with this information. The most interesting idea, according to Reed, from McHargian theory was that of ‘propinquity’, an innate acknowledgement of the proximity, but also the kinship of the environment and it’s actors – aligning the needs of the people with that of the surrounding ecological landscape.

:: image via Gardenvisit

He follows this with the next phase of landscape ecology, best expressed in the work of Richard TT. Forman which “catalyze the emergence of urban-region ecology and planning“, using the concepts of matrices, interconnections, and networks to express exchange of materials. The major contribution of this is the visual, using mapping to acknowledge not a static ecological system, but to facilitate flows that observe an active and dynamic nature. On a practical front, Reed mentions the work of Richard Haag and George Hargreaves as innovative early examples of built projects using these environmental dynamics as generators of form under the mantle of landscape architecture. The realizations contributed to a conceptual shift of ecology from the static (equilibrium theory) to one that included fluctuations in response to disturbance and change.

:: Louisville Waterfront Park (Hargreaves) – image via Hargreaves Associates

The final phase came in some of the early large scale landscape competitions, such as Downsview Park in 1999, which featured time as part of the design brief. All of the entires worked time into the solutions, which laid some foundations of modern landscape urbanism theories of indeterminancy. Not the finalist, but of interest was the proposal from James Corner and Stan Allen, “Emergent Ecologies, which is described on the Downsview site: “The framework consists of an overlay of two complimentary organizational systems: circuit ecologies and throughflow ecologies. These systems seed the site with potential. Others will fill it in over time. We do not predict or determine outcomes; we simply guide or steer flows of matter and information.”

Four Tendencies

The next section discussed the ‘Four Tendencies’ that have emerged into a set of typologies of ecological systems, summarized by Reed here (and hopefully captured in some sense of legibility):

1. Structured Ecologies: Active habits of plant growth, water movement, habitat use – manipulated over time in response to change, factoring in resiliency and incorporating landscape as a dynamic field.

2. Analog Ecologies: Use ecological elements to achieve non-biological products, epitomized in the work of Ned Kahn and Chuck Hoberman.

3. Hybrid Ecologies: Responsive design systems that tap into large scale system dynamics, including human and non-human interaction in space.

4. Curated Ecologies: Structured interactions with dynamics over time, not under specific control, but poked and prodded – designers role shifts as project demands.

The work evolved from the Harvard GSD, particularly the work of Nina-Marie Lister, for a May 2010 event ‘Critical Ecologies’ which synthesized the historical and current practices of biology, horticulture, and anthropology as antecedents to design. (need to find out more on what happened here, as it sounds like a great event with some amazing speakers.

Work of StossLU

In the next part, Reed explained some of the work of Stoss, to give a physical reality to some of the ideas of open-endedness and concepts in action. To provide a framework for these approaches, these were intermixed within a number of larger ideas.

Thicken the Surface:

Using the concept of multiple uses and meanings for land, imbued with both form and performance – but not strictly in a sculptural sense. This best expressed in Riverside Park, in New Bedford, Massachusetts, an eco-park that elaborates the performance aspects of topography, with formal sculptural qualities as a result of the underlying processes.

:: Riverside Park – images via stossLU

Draw on Local Practices:

The project mentioned was the Competition for the Herinneringspark in regional West Flanders, Belgium, which used ephemeral interventions over large spaces for this historical WW II site – specifically focusing on agricultural cycles to highlight specific forms. (sorry, couldn’t track down any pics on this one)

Flexible Spaces for Social Interaction:

Using the Erie Street Plaza in Milwaukee, Wisconsin as an example, mentioning the patterning of materials (lawn and pavement) and the interplay as a randomized surface that allows for a flexibility of uses. The other aspect of interest was the connection to the water table and the fluctuating levels of moisture and the use of steam to melt portions of the snow for year-round use.

:: Erie Street Plaza – image via Architect’s Newspaper

Open Ended Design:

The garden festival in Grand-Metis, Quebec is the example for open-ended design, ‘Safe Zone’ was designed with simple materials in new forms, for a flexibility of uses… a play area, but not prescriptive, rather a safe and injury free surface for experimentation and adaptable play (one as Reed mentions, kids get intuitively, but adults take time to adapt to)…

:: images via playscapes

(more pics here on L+U)

Civic Scale:

A more expansive explanation included the concepts of civic scale, expanding some of the more ephemeral and small-scale interventions into significant projects in urban areas. One example Reed noted was the Fox Riverfront in Green Bay, Wisconsin, which is built above a sheetpile walll, and required the manipulations of various surfaces to accomodate a range of spaces. The stepped benches form seats and chaise lounges, reacting to the different heights of the subsurface conditions.

:: image via Minnesota Public Radio

The overall site also responds to the flooding conditions that come up and over the bulkhead, creating a reactivated civic space while simultaneously incorporating a functional piece of civic infrastructure.

:: image via National Design Awards

Engaging/Recalibrating Infrastructure

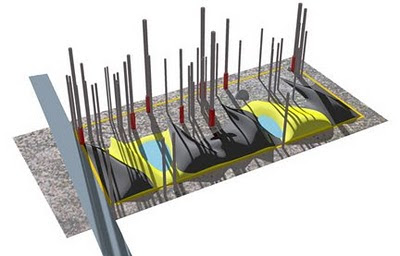

The representative project for this concept was the controversial (locally) competition for capping the Mt.Tabor Reservoirs in Portland. Stoss’s concept was one of the more innovative, blending a new ecology while creating a social spaces.

:: image via National Design Awards

An Integrated Project: Lower Don Lands

A larger example of a project was the competition for the Waterfront and Lower Don River area in Toronto, Canada, which Reed explained in a bit more detail. The concept (the competition eventually won by MVVA) by Stoss offers a chance to provide an integrated approach, with a goal towards both restoration of the Lower Don River and the subsequent urbanization. This river first, city second does resonate with the landscape urbanism principles of new form-making driven by landscape/ecological processes.

The condition of the existing 90 degree bend of the river, and the need for a more modulated river/lake interface required designing a river, which had both a performative and aesthetic requirement. This involved a couple of what Reed refers to as principles and flexible tactics:

1. Amplify the Interface: between the river ecosystem and the restored estuary

2. Hybridize the Parts: changes between armored and porous materials, restoring the marsh condition and then letting the ecological systems take over, which provides flood control while creating spaces for urban activities.

3. Modify the Harbor Wall: establishing a vocabulary of marshes and channels, which form courtyards as catalysts with flexible programs.

4. Unique Building Typologies: Flexibility of form, and flow of landscape across spits and islands, then up the faces of the buildings – green machines.

:: image via Penn Design

Stay tuned for a synopsis of the Panel Discussion coming in a separate post.

Thanks to all the great folks at UW, as well as Chris, Howard, Randy, and Peter for the great after lecture discussions and dialogue.

NOTE: Anyone in attendance wanting to clarify, contest, or expand any of these thoughts, feel free to comment. Look forward to hearing more.

You know he doesn’t pay his interns…

Milwaukee……spellcheck.

Yes, having grown up in the great plains, the Wisconsin -ee version was always rote – so for the past 14 years I’ve been regularly mis-spelling our local version – south of Portland, which is the Oregonian -ie version.

Milwaukie, Milwaukee – alas both are firmly entrenched in my spell-check as valid… but thanks for the heads up. Will make sure we’re talking Wisconsin.