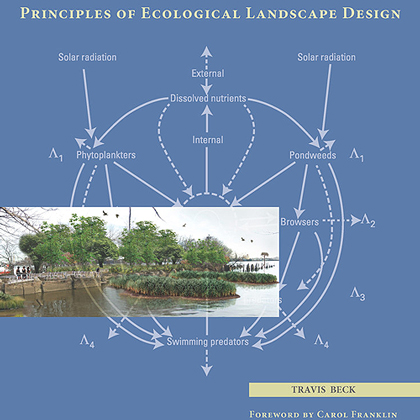

I’ve been busy reading through the new book ‘Principles of Ecological Landscape Design‘, an interesting addition to the growing literature blending science and design in a practical sense. Author Travis Beck is a landscape architect and currently the Landscape and Gardens Project Manager at the New York Botanical Garden, and he has used his horticultural and design background to illuminate some of the connections, challenges, and opportunities from designing ‘ecologically’.

As seen on the web blurb:

“This groundbreaking work explains key ecological concepts and their application to the design and management of sustainable landscapes. It covers biogeography and plant selection, assembling plant communities, competition and coexistence, designing ecosystems, materials cycling and soil ecology, plant-animal interactions, biodiversity and stability, disturbance and succession, landscape ecology, and global change. Beck draws on real world cases where professionals have put ecological principles to use in the built landscape.”

It’s too much to cram into one post, so I’m going to be regularly updating on the information in bits and pieces, starting with this intro. As mentioned by Carol Franklin in the Preface, the book builds on a small but important foundations of landscape ecology from Richard T.T. Forman in such books as Land Mosaics: The Ecology of Landscapes and Regions, and Landscape Ecology Principles in Landscape Architecture and Land Use Planning – both of which are more accessible in terms of ‘designer-friendly’ science. Rather than take on the entire ecological spectrum, the focus of Beck on the horticultural, particularly the translation of plant ecology into planting design, is important, because the focus makes it a very useful resource for landscape architects and designers.

The Introduction offers some context for the book, with Beck outlining our complicated history with the concept of landscape and the roots in the pastoral and picturesque. He mentions Olmsted and Vaux and their “Greensward” Plan for Central park, inspired by Capability Brown’s English countryside. The hidden illusion of ‘nature’ and the massive human effort involved is a common theme in historical references to style that we’ve battled with for over 100 years.

Now, we’ve evolved to a more nuanced idea of ‘urban’ nature, but still struggle with the idea of what the poster child of this new style being Field Operations’ High Line, the highly designed and maintained landscape atop the abandoned elevated rail corridor. As Beck mentions, we evocation of ‘spontaneous’ vegetation required significant engineering and requires on-going maintenance to keep viable – not unlike the Central Park from a century and a half earlier.

As urban landscapes, it is expected that we can’t perform pure ‘ecological’ restoration, but is there a more informed and ecologically appropriate approach? This is the premise of ‘Principles’, as Beck asks “What if, instead of depicting nature, we allowed nature.” (3) This is done through ecological landscapes, not the restorative but the actively design, “that are imagined and assembled by people.” (4)

The relevance to our better understanding of design and science can be framed in numerous ways. One is the ecological view, that less input will be more ‘sustainable’ and a landscape that is more ‘fitted’ to it’s context would be more resilient and regenerative, or as Beck posits to be “flexible and adaptive and continually adjusts its patterns as conditions change and events unfold.” (5). Second is a economic view, as it would be less expensive to build and maintain these sites, which allows for more green in cities, and better spaces. Third is a professional view – one that imagines a true and relevant blending of design and science would free us from the art v. science battles and the criticism of create hollow, misinformed or ’boutique’ ecologies. It would also enable us to create landscapes to aid in larger scale assemblies (cities) or to combat global catastrophes (climate instability).

With the proper tools, designers are freed to have explore formal possibilities with real and testable constraints. This greater understanding of where we plant, what we plant, and how they interact, gives us a solid foundation to justify new design modalities and forms of expression. This, coupled with an understanding from clients and maintenance staff of the the long view of how sites will evolve and grow over time, expands the possibility of a new paradigm shift in our use of plants.

As Beck mentions:

“An ecological landscape knits itself into the biosphere so that it both is sustained by natural processes and sustains life within its boundaries and beyond. It is not a duplicate of wild nature (that we must protect and restore where we can) but a complex system modeled after nature.” (5)

The underlying theme of ‘self-organization’ as an important aspect of this process, allowing for continuation without continual input and human agency. This regenerative quality of establishing a self-sufficient landscape that meets all of it’s needs is important in ecological restoration to determine success. It is more difficult to thing of this in terms of managed and urban landscapes which are extreme conditions that lack analogs in nature.

The range of landscape contexts and types, along with aesthetics, safety, financial, and other considerations will create a continuum of landscapes that will lend themselves to varying degrees of self-sufficiency. Some will be able to thrive with little to no additional inputs, while others will need higher levels of care. Our expanding set of tools driven by scientific knowledge, allows us to more directly engage in the ‘fitness’ of our materials to fill the roles we assign them, which is inherently different from our current approaches. Principles of Ecological Landscape Design, it seems, may allow us to expand the toolbox in even more robust and novel ways.

More on initial chapters upcoming.