I was really excited to learn about the publication of this book Landscape Observatory: The Work of Terence Harkness (2017, Applied Research & Design). Having earned my undergraduate degree in Landscape Architecture at North Dakota State University, our design milieu often focused on the sprawling plains, with design exercises that took us into the realms of prairie restoration, natural resource management through mine reclamation, interpretation of working (agri)cultural landscapes, and sometimes even to the fantastical. However, there was often a feeling of a dearth of solid big “D” design models and reference projects that focused on the plains landscape and that, frankly, felt like landscape architecture we were seeing in design magazines. I was also fortunate to have a professor, Matt Torgerson, who hailed from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and introduced our class to the work of Harkness. The influence of his work and process strongly influenced me then, and has stayed with me to this day.

The slim and graphics packed book is edited by M. Elen Deming, the book includes a number of contributors, including Molly C. Briggs, Brenda Brown, Frank Clements, Kathleen Harleman, Doug Johnston, Ken McCown, Robert B. Riley, Amita Sinha, James Wescoat. Each reflect on the work in specific ways, with Deming sewing it up into a readable composition. It isn’t a book you need to read front to back either, as it was fun to zoom into some essays and then come back to others for more context and a broader range of projects and background.

The short blurb from the publisher’s website sums it up nicely:

“The modernist history of landscape architecture is deeply marbled with veins of regional and phenomenological sensibility. Master designer Terence G. Harkness reflects this sensibility in every region he inhabits – whether the foothills of northern California, the high plains of North Dakota, or the lost prairies of east central Illinois. The long arc of his eco-revelatory work and teaching is brought to light by this presentation of Harkness’s most significant works, drawings, plans, models, and photographs. Contributors to the book chronicle Terry’s development and values and position him within the currents of contemporary landscape discourse. The book examines Harkness’s place-based pedagogy and his role as a design mentor and model.”

It’s always a delicate balance of image to text, and this has a nice mix of the prototypical Harkness sketches, vignettes and project photographs, making it not feel too dense but also imbuing it with some substance. Large page spreads highlight sections, and plenty of plans punctuate text by the various authors, along with lots of interview narrative with Harkness in his own words.

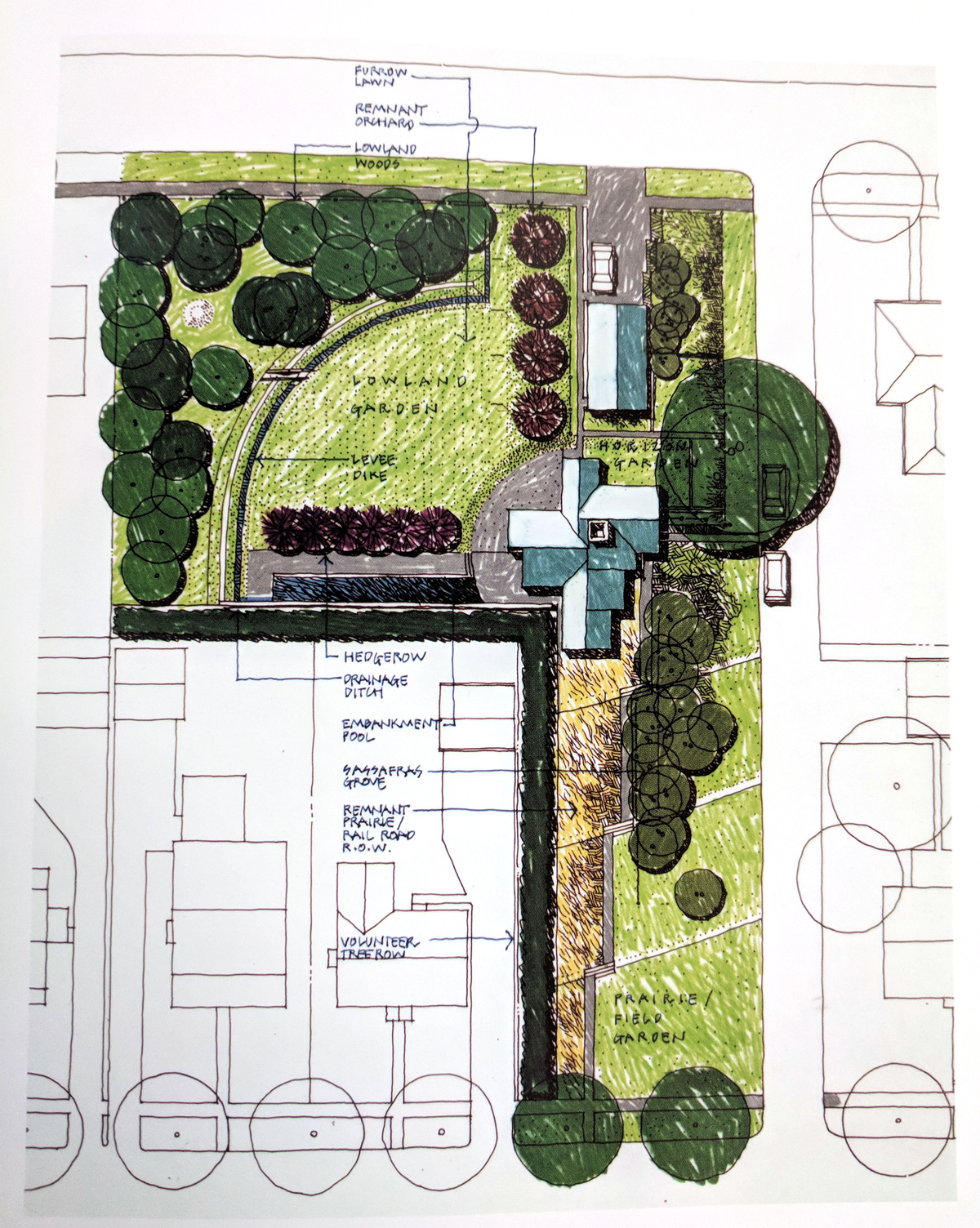

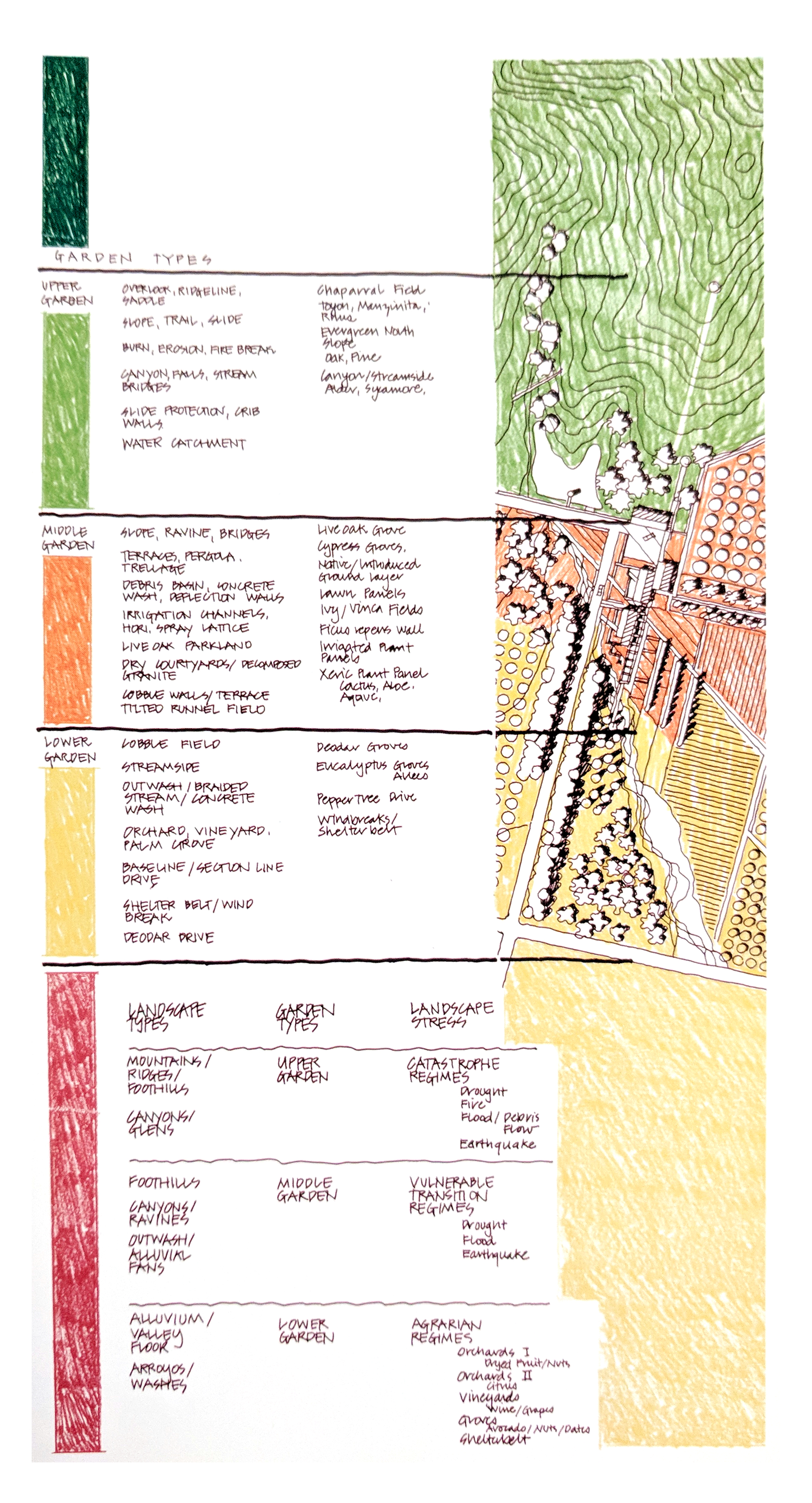

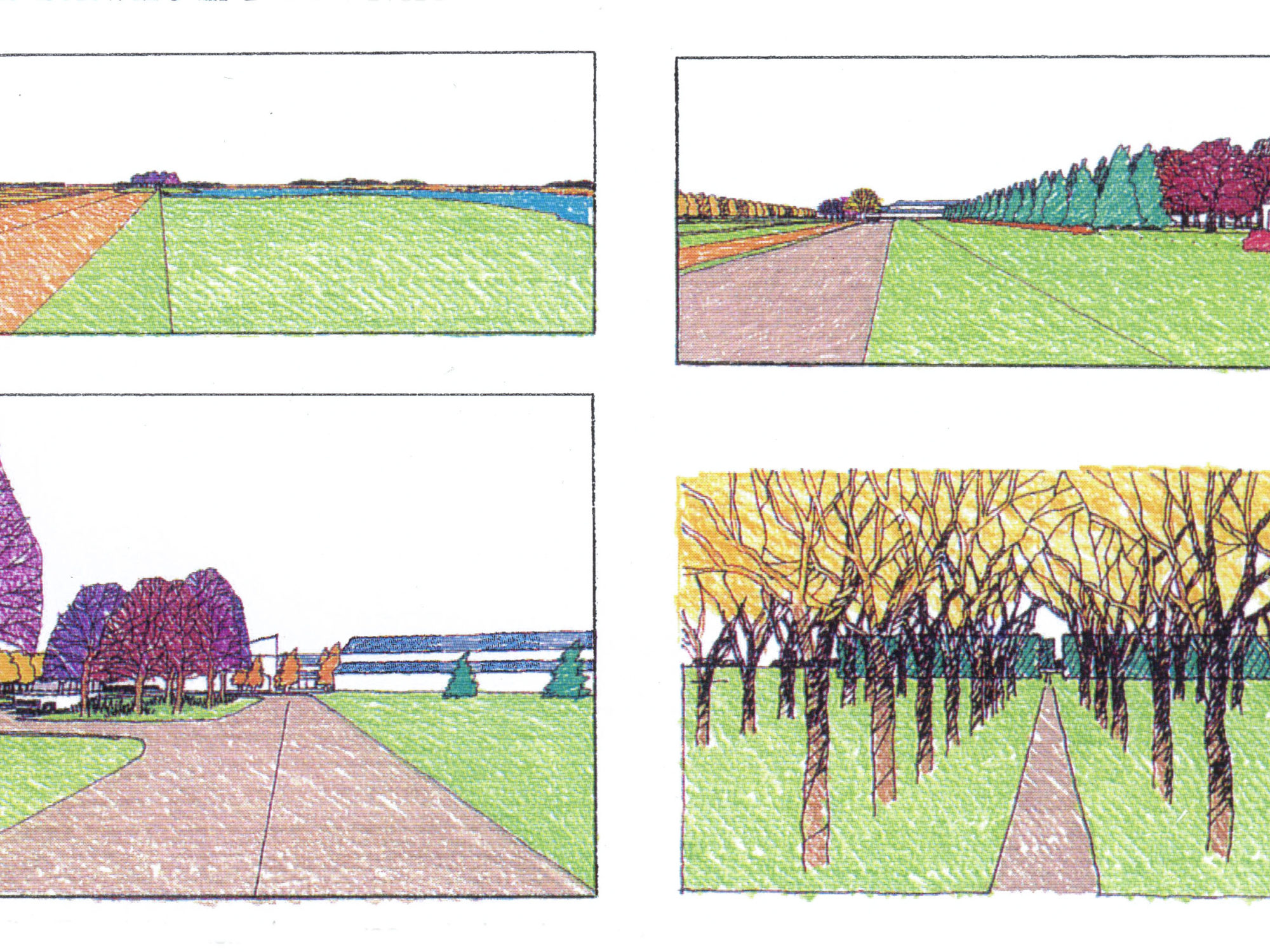

The above plan graphic and perspective study for “An East Central Illinois Garden” from 1986, had a profound influence on my work as a student, both in how to organize process using annotated vignettes, and the ability to relate plan relationship (which is always too much of a focus for students) to three-dimensional space. This was particularly more challenging in an early digital age where Sketchup, Rhino, and Revit were nascent and non-existent. The ease of one-point perspective studies and simple gridding for depth allowed the ability to quickly get out of the plan relationships and see the experiential.

The modern plan relationships did get me, as I was equally influential graphic of the time is the “Site Plan for A Suburban Garden, which from the book had a site “adapted from Harkness’s own home and garden in Champaign, IL)” (45). I’d not seen it in color before, only black and white) with it’s formal configuration relating to the Jeffersonian grid, and the layered design moves compacting multiple landscape types into a composition through foreshortening and simple cross-axial relationships.

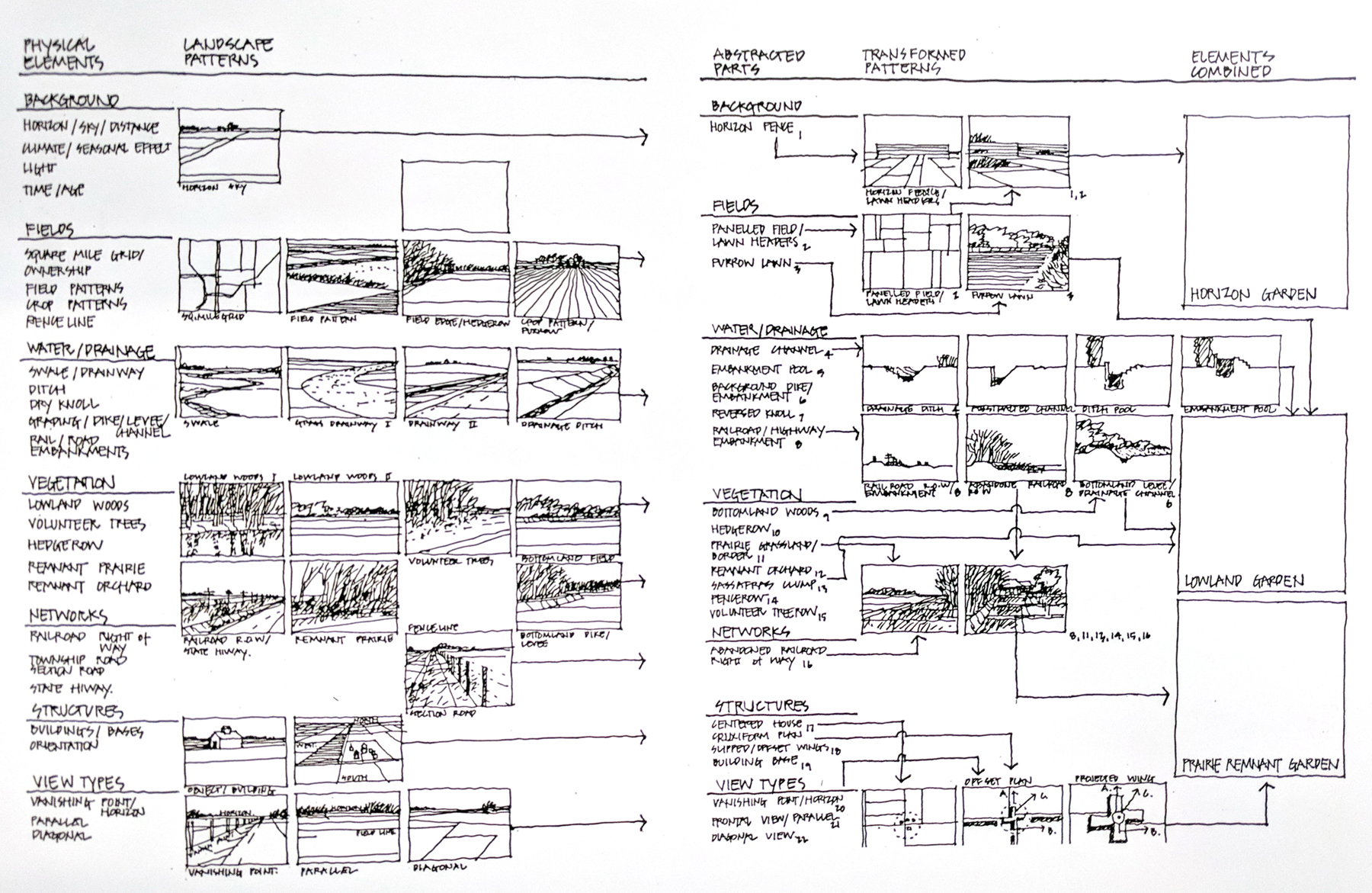

From the chapter by Douglas Johnston, “The Thinness of Things: Illinois Gardens” this idea is captured: “Terry Harkness, a keen and careful observer of the landscape, sees much more in the apparent plainness of the Illinois landscape. He sees the landscape not as a recipient of imported design forms but as a source of unique form, literally grounded in its place. Harkness’s designs for east-central Illinois are not based on conventions of what a landscape should be, but a celebration of what the landscape is. Abstracted and magnified, fields and groves become geometric planes. Where roads and hedgerows border the fields, insertions of edges mark the planes on the ground while hedges and fences frame them. Channels and roads are the figurative and literal expressions of drainage and movement with the horizon separating or joining the earth and sky.” (39)

This design vocabulary is referenced by the sketch studies like the one below (Analysis of landscape elements, patterns, abstraction and transformation for An East Central Illinois Garden), The study breaks down the design from above, blending landscape elements, both large (such as distant views and patterns of prairie landscape) and small (looking at subtle topographic manipulations to foreshorten, frame, and contain). I could inevitably unearth notebooks of similar studies use in college and after to articulate a visual, regional language of landscape that resonated with me personally because, rather than trying to adapt visual and design methodology from it was operating in the same landscape context so had immense relevance.

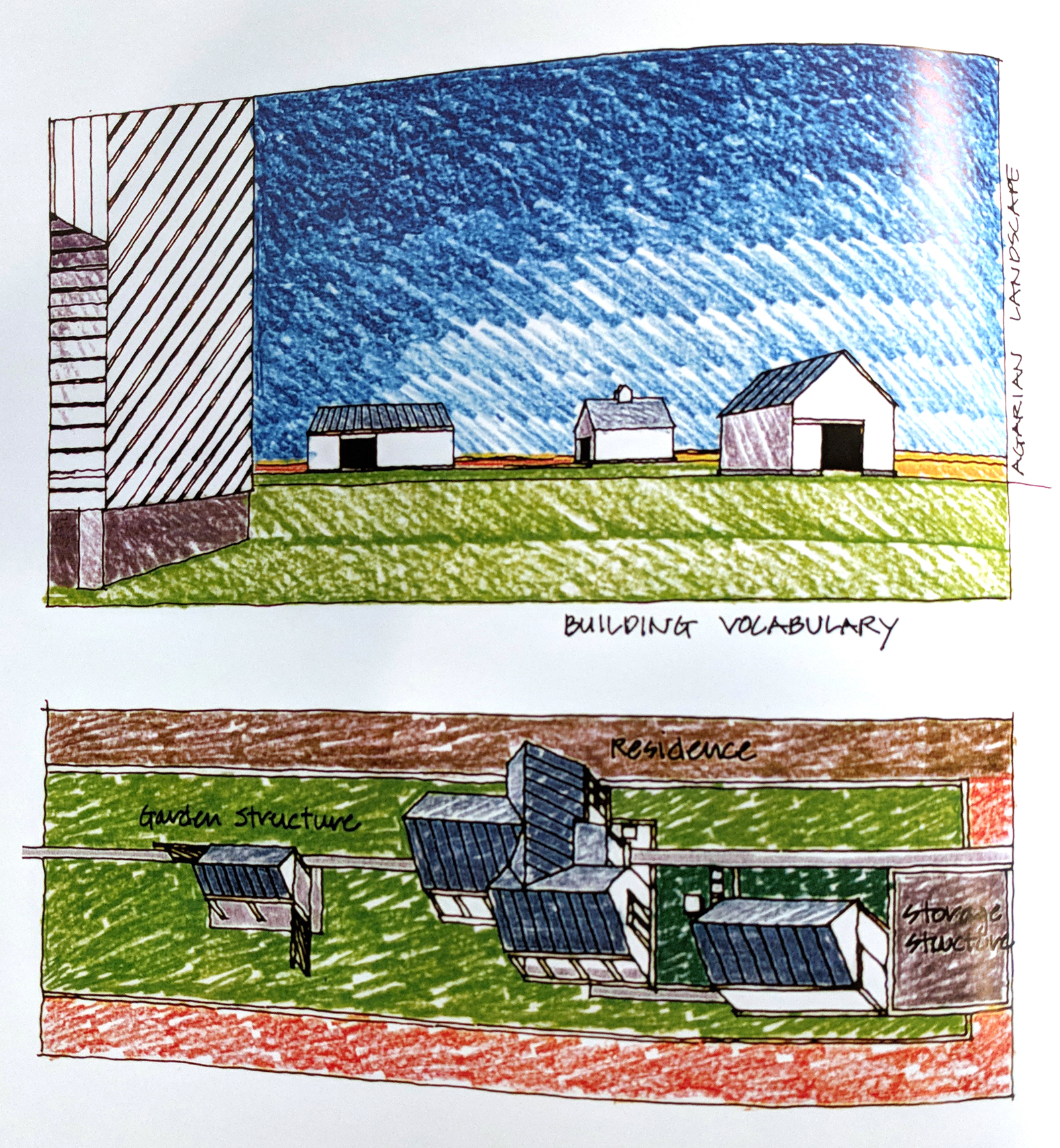

In a style well suited for the horizontal, as seen below in an undated study of ‘Rural Prototypes/Organization’, which showed “Studies of vernacular forms of the agrarian Midwestern landscape.” The razor sharp flat horizon line, immense sky and the strength of perspective all tied into understanding the landscape, which in turn yields better design solutions.

Moving to the Pacific Northwest after college and reading much about NW Regionalism, it became evident that what I had learned was a method for understanding a landscape, and appreciating the subtle Plains Regionalism. And while the context of the mountains of my new home was different (and at times claustrophobic making we flee to Eastern Oregon) the . I hadn’t seen the work of Harkness outside of the plains context, so the Chapters on the Foothill Mountain Observatory and the Taj Mahal Cultural Heritage District were informative in the methodology transferred to other locations.

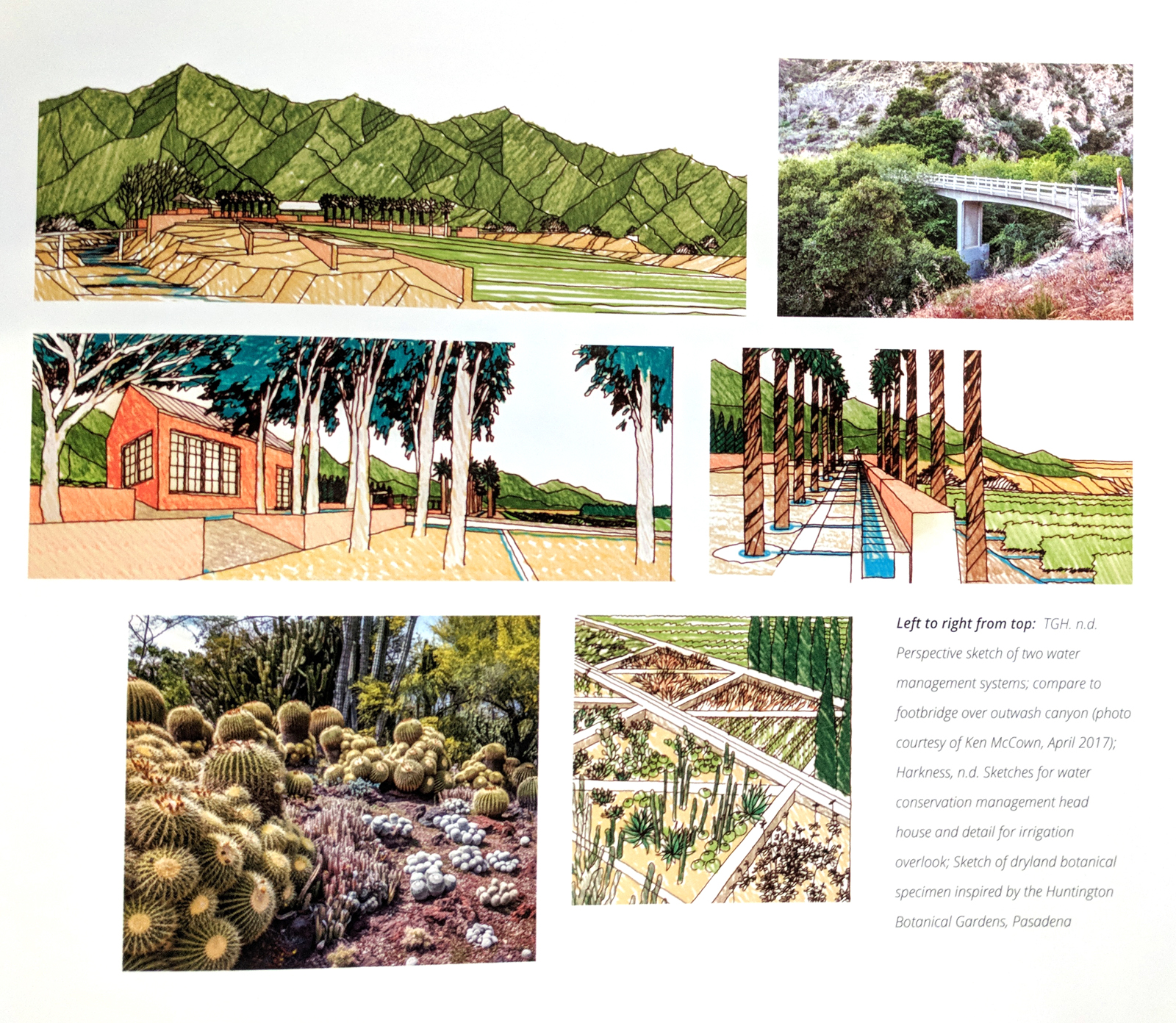

The sketches of landscape elements and capture this terrain in new ways (or for Harkness, having grown up in Los Angeles, in old ways), looking a dryland plantings, and outwash canyon landscapes well outside the prairie ecosystem. The Foothills project, from the chapter by Ken McCown, “embraces the complex conditions of landscape through design, not interpretation or metaphor. The observatory is not a representation of regionalism through design, it is a framework of circulation and program to integrate people with natural systems, agriculture, and infrastructure. The design helps recalibrate people to their landscapes, not as nature, or garden, or infrastructure, but as an integrated whole of elements and systems evolving over time to shape and reflect culture.” (53)

The final image of a garden typology, in it’s simple complexity, it made me re-assess my relationships with my own process. The concept of the book encapsulating a “Landscape Observatory” is fitting, as explained by Deming and Briggs, in “his keen powers of observation, analysis of regional patterns, and best transformation of landscape cues into new representations of place, Harkness’s body of work may be characterized as a landscape observatory.” Further, elaborating on this connection of learning is a “Pedagogy of Seeing”, in which “…the notion of the observatory speaks to Harkness’s penchant for design as a form of teaching – to compel us to ‘come to attention’ and really see the landscape we inhabit. The objective of such precise perception is not limited to ecological process but, rather, leads to holistic comprehension of landscape genesis, cultural co-evolution, and social formation. Not quite an ecologist, yet far more than a formalist, Harkness’s design forms invoke the interdependence of regional cultural history taking place within the biophysical landscape.” (11)

The impact goes beyond just a ‘prarie’ of ‘midwest’ school, to elaborate on a relevance beyond just a local regon. Again from Johnston,

“Terry Harkness’s designs have an authenticity and elegance grounded in their place. His work is always original, crafted by a discerning eye that delights in bringing out the beauty in things most of us overlook. His gift is to find the poetry in common landscapes all around us – and to distill the essential qualities and flavors and elements that distinguish them from anywhere else in the world.” (45)

Admittedly this review is more about the influence of Harkness on my own design journey, rather than a look in depth at the book. The texts vary, painting a picture of a practice, plenty of biographical notes and lots of great info on . For me, in the end, it resonates as a case study in place, vernacular landscape, and regionalism. Regionalism in design is a tricky item, as it can be wielded by the uninformed to create trite, derivative designs. In landscape this perhaps easier to manage as the tools of plant, soil, and material emerge from the landscape itself, but the Prairie landscape in particular, in its mix of immensity and subtlety, challenges the best designers to attain good design that is fitted to this unique place.

Dealing with this dilemma is Harkness’s gift, as Riley mentions in the afterword: “Terry is probably best understood as a regionalist designer. Regional design is one of those concepts always hanging about on the fringes of architectural and landscape architecture, never quite becoming fashionable nor a dominant concern. It is not easy to precisely identify what makes Terry’s work diffferent from the mundane historical kitsch usually advanced as regional. After over three decades of knowing and working with him I still can’t quite express that particular essence that sets it apart. His work is not literal. Neither is it an abstraction clothed in au courant cant.” (101)

I’ve not seen his built work, as the designs for projects like the “Prairie Slope Garden at Temple Hoyne Buell Hall at UICU (seen above) were outside of my range, and designs for the International Software in Fargo came after I graduated in 1997. However, I imagine subsequent crops of students learning from a vibrant local design example in their backyard (with the hours-long slogs to Minneapolis or Chicago). Further reading of the book, with inevitably yield more insights than I’ve shared here, but Harkness’s passion for detail and place emerges from this text, and re-inspired me to look differently at how I create.

Perhaps practitioners of landscape architecture in this ‘middle’, and specifically the Plains, feel disconnected from the larger discourse due to having less practitioners and documentation and formal models of how to operate in the vast, flat, landscapes in which they design. The theory, work, and methods of Harkness, well documented in this fantastic book, can fulfill this need, and also inform designers from all regions equally.

HEADER: Harkness Sketch – “Distilling North Dakota” via AR+D

Thanks for sharing that, Jason. I was not aware of Harkness’ work. I will, however, need to save some pennies to purchase it. That’s an expensive book!

Keep up the great work!

Thanks Mike. Oh the perils of our profession, where books are printed in such small quantities for our relatively small audience they end up being overly expensive. I’m biased and nostalgic about this on in particular, but its worth a read, especially the unique take on regionalism.

I sat next to Terry at HOK for almost 4 years. Besides the designs, he was great at site analysis and a story, an idea. At HOK; there was “the Three, the Father, Son and Holy Ghost” and Terry was the “Holy Ghost”. I wanted to be a disciple.

Terry was one of my professors at the University of Illinois. I loved his lectures and remember carefully taking notes even on the very last day of one of his lectures. I have those notes to this day -48 years later.

Thanks to his inspiration it led me to an amazing career. I am forever grateful.

Joel Barham

great story Joel – love to hear that. As I only was introduced second hand, i still feel like the inspiration stuck with me as well. thanks!

Terry was one of my professors at the University of Illinois. I loved his lectures and remember carefully taking notes even on the very last day of one of his lectures. I have those notes to this day -48 years later.

Thanks to his inspiration it led me to an amazing career. I am forever grateful.

Joel Barham

I would like to know where the concept of Landscape Observatory originated – where, when and by whom?

Thank you