An amazing resource posted on ASLA’s The Dirt (here) focuses on Design Guidelines for Urban Wetlands, specifically what shapes are optimal for performance. Using simulations and physical testing to investigate hydraulic performance the team from the Norman B. Leventhal Center for Advanced Urbanism (LCAU) at MIT. Led by Heidi Nepf, Alan Berger and Celina Balderas Guzman along with a team including Tyler Swingle, Waishan Qiu, Manoel Xavier, Samantha Cohen, and Jonah Susskind, the project aims to have a practice application in design guidance informed by research. From their site:

“Although constructed wetlands and detention basins have been built for stormwater management for a long time, their design has been largely driven by hydrologic performance. Bringing together fluid dynamics, landscape architecture, and urban planning, this research project explored how these natural treatment systems can be designed as multi-functional urban infrastructure to manage flooding, improve water quality, enhance biodiversity, and create amenities in cities.”

Starting in the beginning by outlining ‘The Stormwater Imperative’, the above goal is explained in more depth, and issues with how we’ve tackled these problems are also discussed, such as civil-focused problem solving or lack of scalability, but also explore the potential for how, through intentional design, these systems “can create novel urban ecosystems that offer recreation, aesthetic, and ecological benefits.” (1)

The evolution that has resulted in destruction of wetlands through urbanization, coupled with deficient infrastructure leads to issues like flooding, water pollution due to the loss of the natural holding and filtering capacity of these systems and the increased flows. However, as pointed out by the authors, this can be an opportunity, as constructed wetlands “can partially restore some lost ecosystem services, especially in locations where wetlands do not currently exist.” (5)

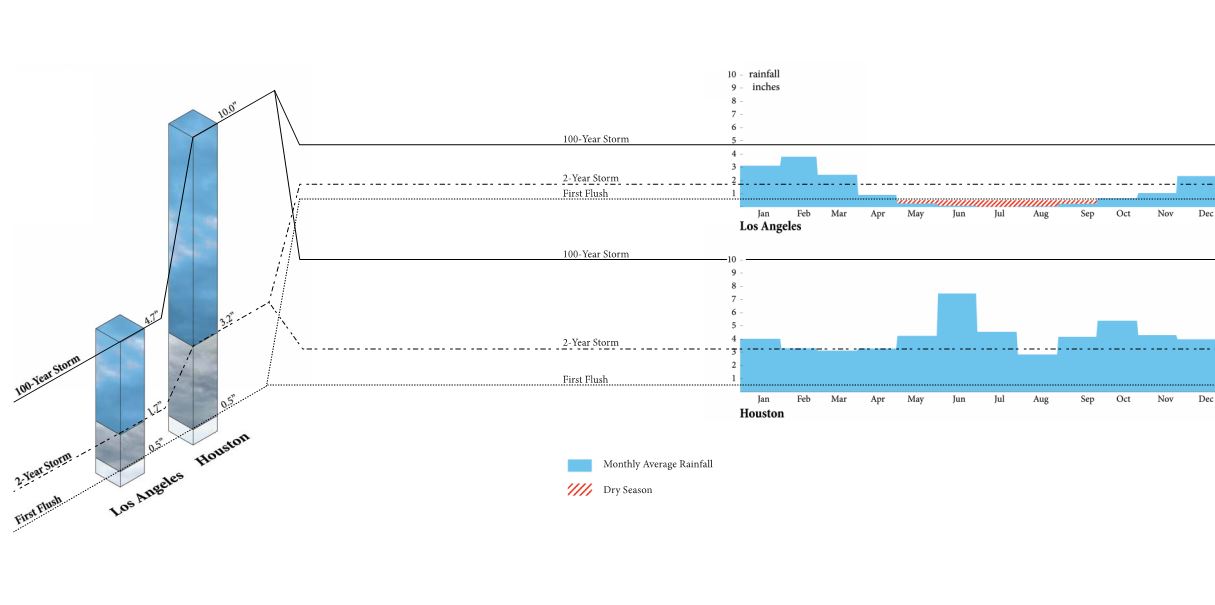

The use of two vastly different case study models, Los Angeles and Houston, allow for some testing to determine the applicability of methods to different ecological, hydrological, and cultural regimes as well. Just looking at the rainfall totals and frequency curves highlights this difference.

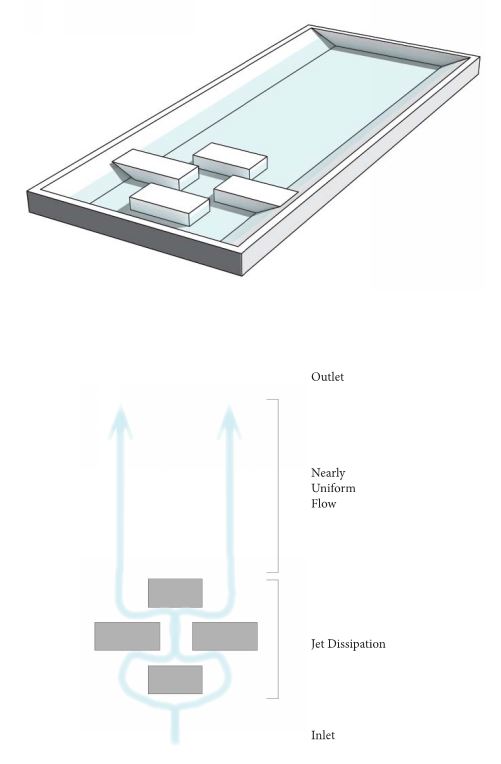

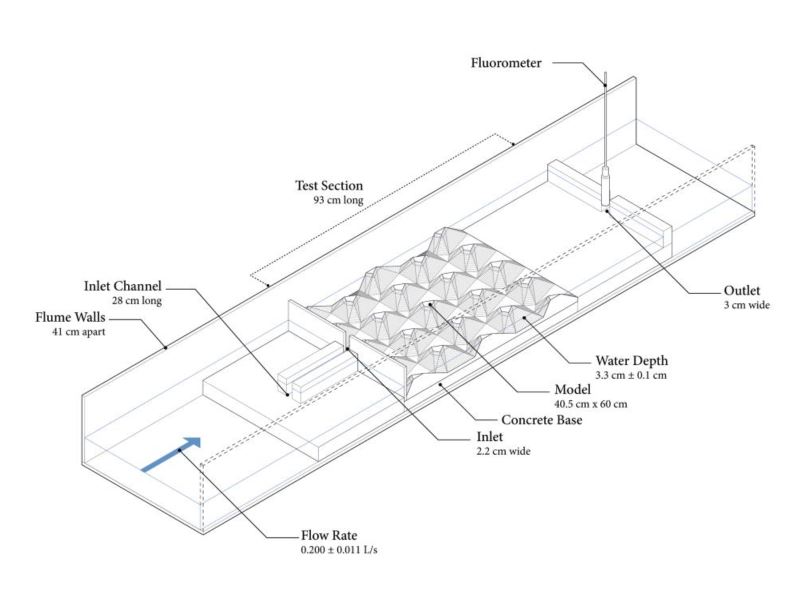

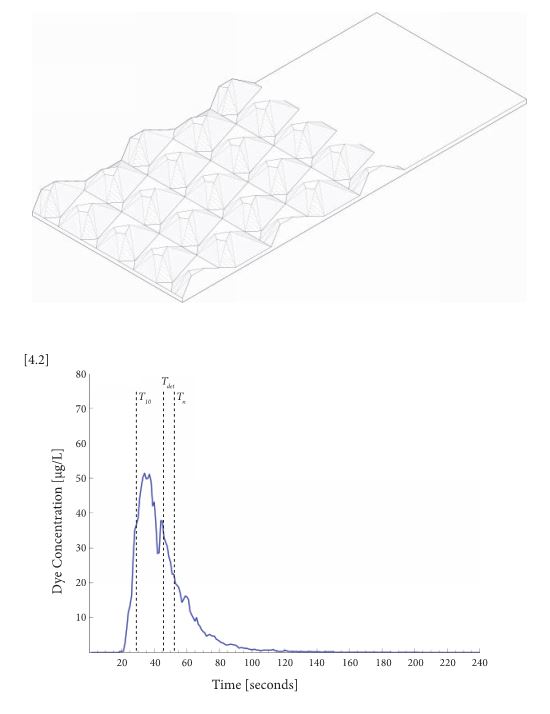

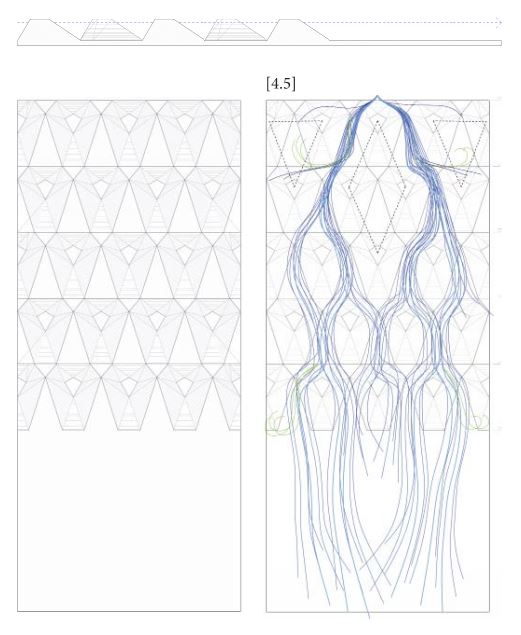

The methodology is explored in the second section ‘Sculpting Wetlands’, which discusses a number of processes for developing typologies, and also how specifics like construction costs and habitat diversity indices were developed. Using casts of different types of forms, these could be introduced into a table model for testing using dye tracers.

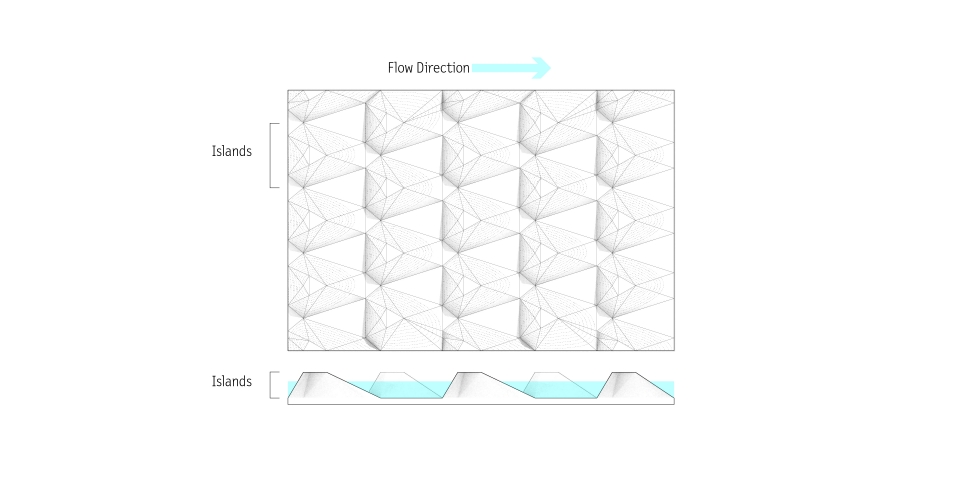

This simple formal arrangement can be modified with additional formal and scalar complexity, with similar testing protocols allowing for comparative measurement. While it is acknowledged that a lot of time and effort has been expended on studying the performance of similar islands by engineering professionals, the difference here is that “ecology and urbanism were not considered jointly with hydraulic performance.” (18) The next step increased the geometric complexity, and forms were cut out using 3D milling machines.

These “explored how island size, shape and placement effect hydraulic flow and provide ecological habitat.” (20) using the flume setup by the Nepf Environmental Fluid Mechanics Lab.

As mentioned, cost and volume were considerations, looking at earthwork along with constructability, which is a consideration when discussing complex grading. Habitat values were also included, with methodology on habitat zones that were created, specifically the mix of Upland, Emergent, Submergent, and Open Water zones and their relative percentages, which were also scored using Shannon-Weaver index.

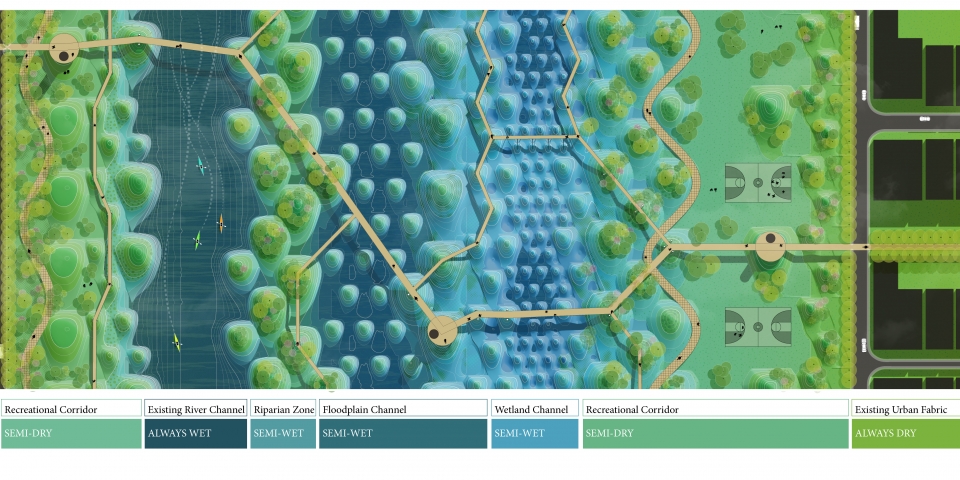

The focus on design also takes into account discussion of modularity and scaling, particularly on applicability to ‘fitting’ these concepts to different project and site sizes and configurations. This is a good segue into the third section, ‘Wetland Urbanism’, shows the flexibility of this methodology in using “modularity and scalability” and how “designers could benefit from a wetland framework that is adaptable for different site size, use, and programming goals.” (59) The section attempts to translate the information into forms and apply these lessons to two distinct Case Study sites: Taylor Yard in Los Angeles and Buffalo Bayou in Houston. Design potentials are elaborated using the terminology “Programmable Topography” which uses the framwork of “Island Corridors” to inform design choice that work for specific habitats, public spaces, and recreational opportunities. This diagrammatic Plan of wetland intervention zones (pp.74-75) shows a visual transect of possible ways this could play out in urban space.

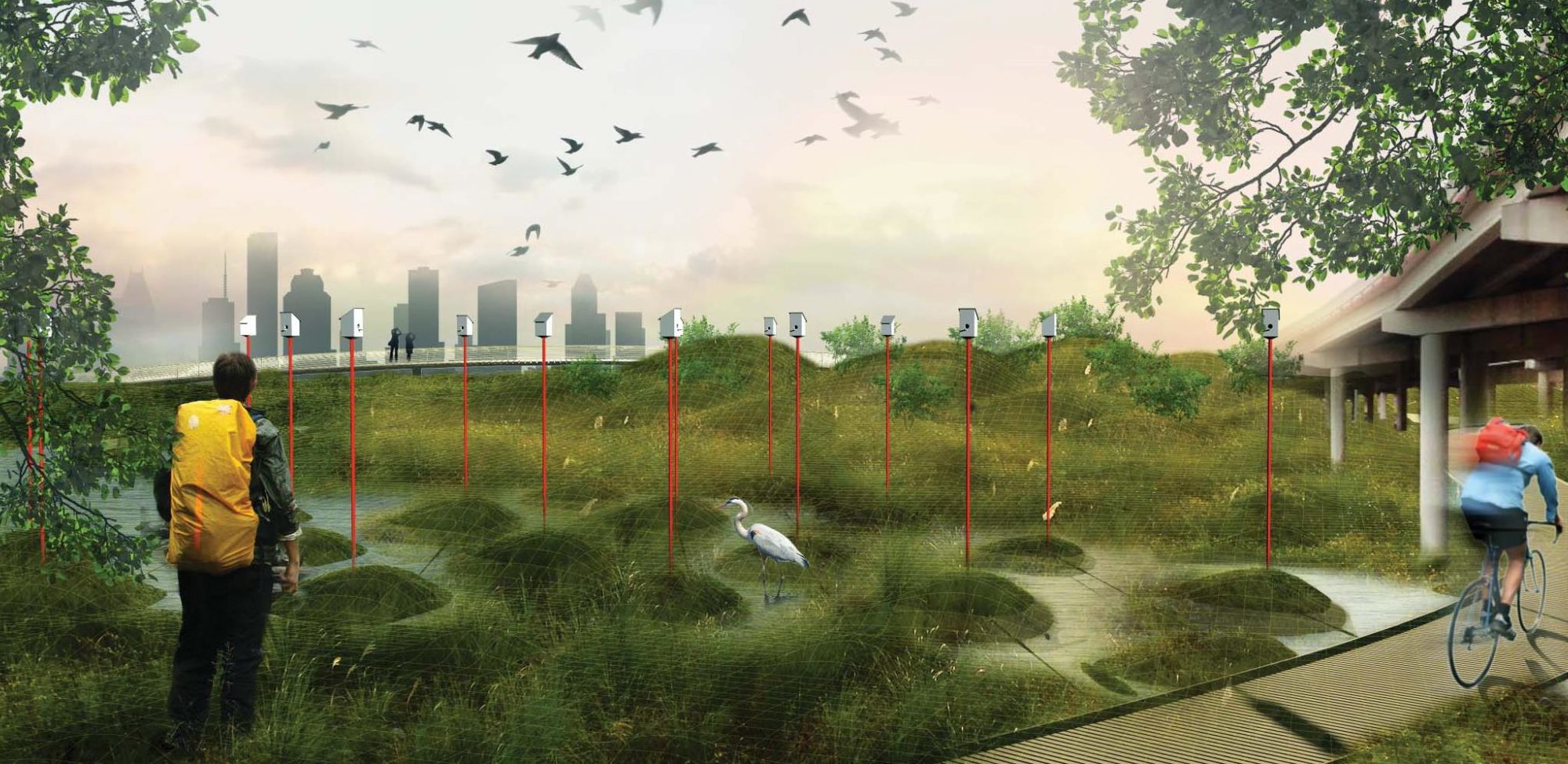

There is some discussion of the design potential in this section, including are a few graphic images that show the character of these elements applied to the case study sites, using sections and perspectives, including the header image of Houston, and this one below of the LA River (pp. 82-83), showing a “floodplain channel with programmed public spaces”.

As a wrap-up, the final section contains a catalog of the 34 topograpy design strategies that were with related information, which acts as the toolkit for balancing function with form. These are more diagrammatic but no less compelling, showing the arrangement, hydraulic analysis, comparative cost, and habitat diversity index.

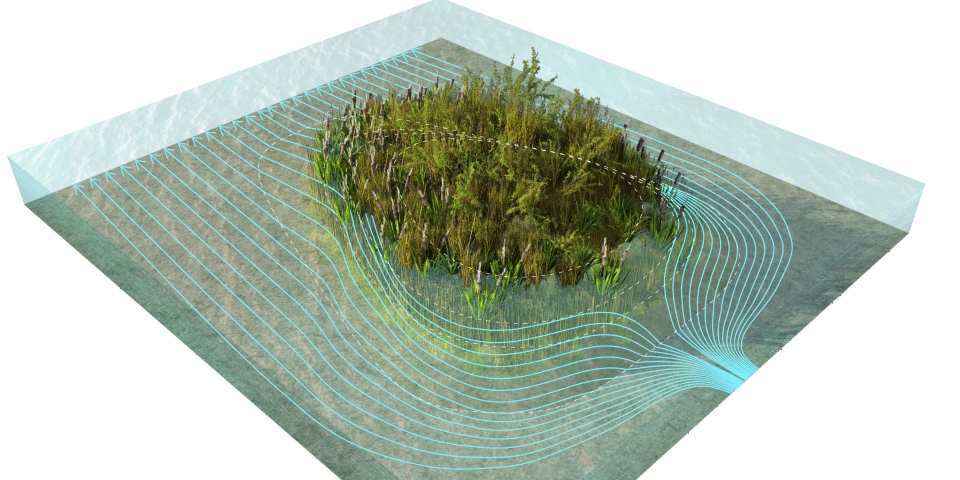

The modeled flow patterns are also interesting, showing the differentiation from fast, regular, slow flows, along with any Eddy’s that were shown in dye testing using the flumes.

It’ll be interesting to see if this report provides the kind of real world information that can influence and inform designers and decision-makers, showing a true link between academic research and projects on the ground. As mentioned in the introduction: “The aim of these guidelines is to inform decision makers, planning agencies, consulting engineers, landscape architects, and urban designers about the efficacy of using ecologically designed constructed wetlands and ponds to manage stormwater while creating new public realms. Our hope is that cities will adopt and apply our findings in projects around the world, opening a door to more explorations of multifunctional urban stormwater landscapes in the age of urban resiliency.” (3)

Check it out and see what you think. The report is available as a online version via ISSUU or via PDF download from the LCAU site, where there are also some additional resources. All images in this post are from these reports and should be credited to the LCAU team.

HEADER: “Rendering of Houston wetland channel showing ecological wetland, conservation areas, and recreation trails” p. 90-91